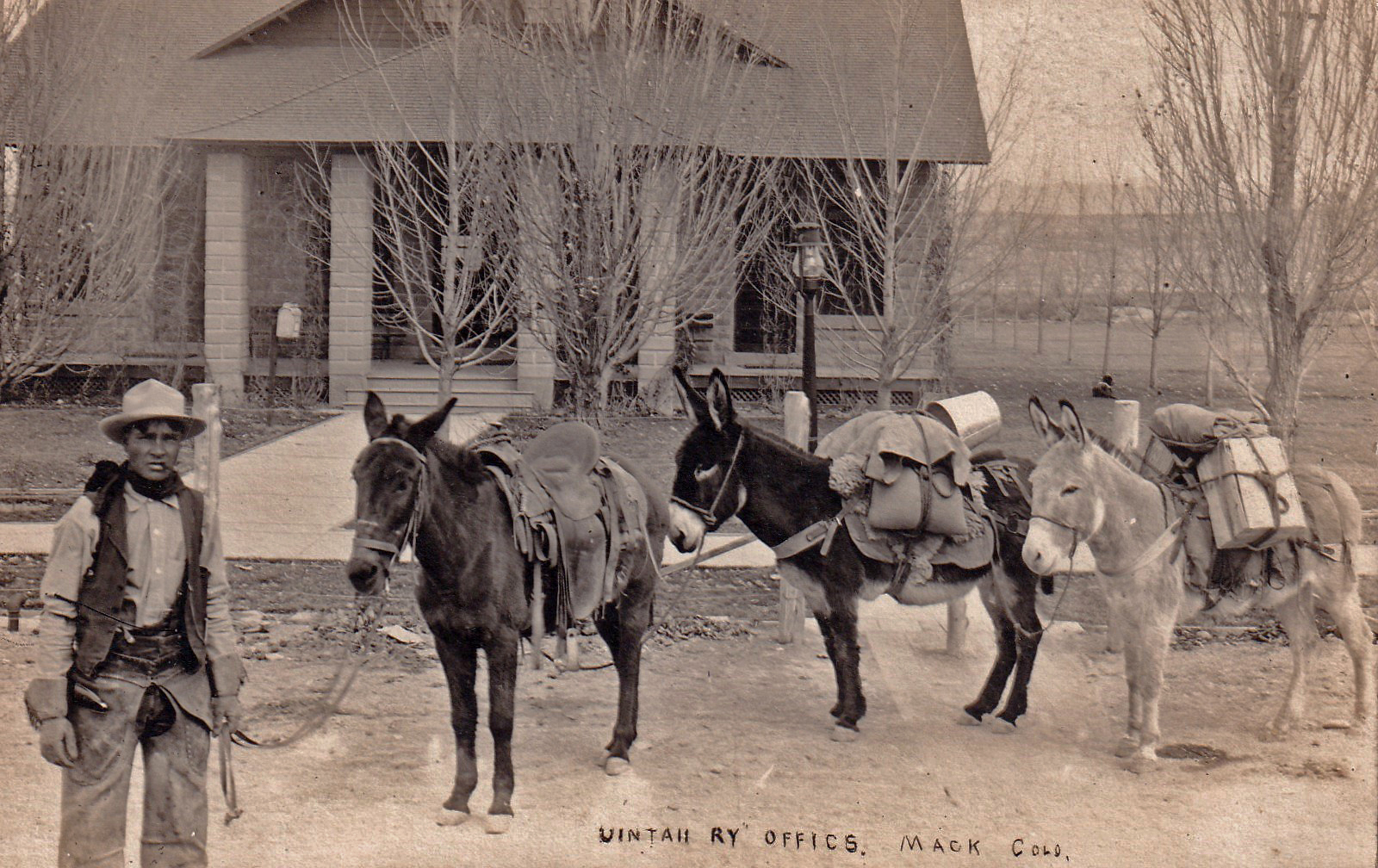

I wish I knew more about what I was looking at in this photo to know what mission this cowpoke was on with his horse and burros, as he stands in front of the Uintah Railway offices in Mack. Mack, founded in 1904, is an unincorporated community in Mesa County with a current estimated population of 1470 residents, and located about 10 miles east of the Colorado-Utah border. It sits about 19 miles, as the crow flies, north and west of Grand Junction. The town was named for John W. Mack, president of the Barber Asphalt Paving Company and the Uintah Railway Company.

Mack owes its birth to gilsonite. Gilsonite, more technically known as asphaltite, is a highly combustible, naturally occurring, soluble hydrocarbon. In its weathered form it looks like coal and when broken open reveals shiny surfaces resembling obsidian. Often called a natural asphalt, gilsonite has hundreds of industrial applications in addition to the manufacture of asphalt, and is found in oil-bearing sedimentary basins, often in conjunction with oil shale. Discoveries in the U.S. beginning in the nineteenth century revealed great quantities of the stuff (an estimated 45 million tons) in the Uintah Basin. The latter is a geographic depression in eastern Utah covering 456,705 acres, stretching nearly 60 miles in an east-west direction, and featuring hundreds of glacier-formed lakes and Utah’s highest peaks.

The year 1869 saw the first documented mining in the U.S. of what would become known as gilsonite when John Kelly, the blacksmith at the Whiterocks Indian Agency (in what is now the state of Utah) asked some Utes to bring him coal. What they brought him looked like coal, but it was soon apparent that it was something far different, for when Kelly heated the substance, it became so hot it nearly burned down his smithy. It turns out this material was not unheard of — some samples of it had been sent to the New York Columbia College School of Mines in 1865, and there were explorers and prospectors who had known of its existence.

An important player in the story of gilsonite is Samuel H. Gilson, for whom gilsonite is named. Gilson, a native of Illinois, came west with his brother, James, in search of gold in 1850. They weren’t successful and subsequently turned to ranching, and by 1870 had established the Mountain Ranch in the Sevier River Valley in what is now the state of Utah. In the course of managing this ranch, it is thought that Samuel either came across an outcropping of what would become known as gilsonite or had it shown to him by local cattlemen. In any event, Samuel and another man, Bert Seaboldt, took an intense interest in the material. They conducted experiments with it, developed uses for it and formed a partnership, which in 1886 became known as the Gilsonite Manufacturing Company. The next year they joined with a mining engineer named Charles O. Baxter and renamed the company the St. Louis Gilsonite Company. . In 1889, a St. Louis firm bought out Gilson’s interest in the enterprise, and the result was the Gilson Asphaltum Company, which became a leading producer of “gilsonite,” as it came to be known.

The earliest organized gilsonite mining in the Uintah Basin depended on freight wagons to haul the gilsonite roughly 100 miles to the Rio Grande Western (later to become the Denver and Rio Grande Western) Railway depot in Price, Utah. However, this was such a slow means of transport that that the Barber Asphalt Paving Company (controlled by the Gilson Asphaltum Company), decided to build a narrow gauge railway, which would be named the Uintah Railway, directly from the gilsonite fields near Dragon in the Uintah Basin to an existing Rio Grande Western standard gauge line in western Colorado. The spot on that line acquired by Barber Asphalt would be the spot where the company built the town of Mack. Once the Uintah Railway was in place, the Mack depot would service the Uintah’s narrow gauge track, which ran on its north side, and the D&RGW’s standard gauge track, which was ran on its south side.

Construction of the Uintah Railway began in the fall of 1903 and, depending on which you account you read, took approximately one to two years to build. It required laying track over the 8,437-foot Baxter Pass, which formed a divide between the Green and Colorado River drainages. The total cost was $175,000, with savings realized through the purchase of used ties, rails and rolling stock from an abandoned Rio Grande Western narrow gauge line. The Uintah line, eventually totaling 64 miles, would require some of the steepest grades and sharpest curves ever built for a U.S. railroad. When going up the pass on the Mack side, one encountered five miles at a 7% grade; on the other side was six miles at a 5% grade. One curve on the pass, called Moro Castle, originally had a 81 degree bend to it, though that was later re-built to 60 degrees. Of course there was humor about these extremes: It was said that some curves were so sharp the engineer could shake hands with the conductor in the caboose, and one railroad worker back then claimed the Uintah’s only straightaway had three curves in it.

As mentioned, the Uintah Railway was of narrow gauge, in this case, 36 inches. Though narrow gauge utilized smaller locomotives with a smaller load-bearing capacity than standard gauge, it was better adapted to steep and rugged terrain than the longer and wider standard gauge locomotives. To best match narrow gauge equipment with geography, the Barber company established two points where locomotives could be swapped for the trip over the pass. On the Mack side of the pass Barber established the town of Atchee (named for Ute Chief Atchee, a half-brother of Chief Ouray’s wife, Chipeta) and on the other side of the pass it was the town of Wendella (which I believe was also established by the Barber company). For the flatter terrain leading out of Mack, a faster locomotive would be used. Then, in Atchee, which was 28 miles out, that locomotive would be swapped for a shorter, stronger locomotive to go over the pass. On the other side of the pass, that locomotive would be swapped at Wendella, which was seven miles below the summit, for a faster locomotive to complete the run into Utah. And vice versa. The running time up or down Baxter Pass was 50 minutes, and the operating rules strictly forbade attempting it in a shorter time.

The Uintah transported the gilsonite on open flat cars, and, because of its flammability, stacked it in wet hundred-plus-pound canvas sacks. The railway also carried passengers and mail, although I don’t whether the latter were transported along with, or separately from, gilsonite shipments. At its peak, the railway owned 11 engines, 2 combination baggage-passenger coaches, 3 former Pullman sleepers, 12 livestock cars, 24 gondolas, 18 boxcars, and 71 flat cars. There was lunch for passengers who brought their own.

With the introduction of better roads and heavy trucks in the 1920’s and 1930’s, transport by trucks became less costly than transport via rail, and in 1938 the Uintah Railway was abandoned. Atchee and Wendella are now ghost towns.

REFERENCES:

- “Asphaltite,” Wikipedia.org at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asphaltite

- “Atchee, Colorado, from above,” Historical Photos of Fruita & Western Colorado (Facebook) at https://www.facebook.com/HistoricalFruitaPhotos/posts/803732200055007

- “Best Places” at https://www.bestplaces.net/people/zip-code/colorado/mack/81525

- “Distance from Mack, CO to Grand Junction, CO” Distance Between Cities, at https://www.distance-cities.com/search?from=mack%2C%20colorado&to=Grand%20Junction%2C%20Colorado%2C%20United%20States&fromId=0&toId=3313&flat=0&flon=0&tlat=39.0639&tlon=-108.551

- “GILSONITE – AN UNUSUAL UTAH RESOURCE,” by Bryce T. Tripp, July 2004, Utah Geological Survey at https://geology.utah.gov/map-pub/survey-notes/gilsonite-an-unusual-utah-resource/ .

- “ GILSONITE PEDIA,” Pars Universal Bitumin at https://www.minepars.com/index.php/gilsonite-pedia/

- “High Uintas,” Forest Service, U. S. Department of Agriculture at https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/uwcnf/about-forest/districts/?cid=fsem_035477

- “History of American Gilsonite Company,” American Gilsonite, at https://www.americangilsonite.com/about-us/history/

- “ Mack, Colorado,” Wikipedia.org at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mack,_Colorado

- “Mack Colorado, Uintah houses,” Digital Collections, Denver Public Library, at https://digital.denverlibrary.org/digital/collection/p15330coll22/id/10479

- “MINING AND TRANSPORTATION, 1890-1920,” Chapter VIII, An Isolated Empire: A History of Northwest Colorado, BLM Cultural Resource Series at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/blm/cultresser/co/2/chap8.htm

- Sam Gilson Did Much More Than Promote Gilsonite,” History Blazer by Jeffrey D. Nichols, May 1995, HISTORY TO GO at https://historytogo.utah.gov/sam-gilson/

- “Uinta Basin,” Wikipedia.org at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uinta_Basin

- “Uintah Hotel, Dragon, Utah, “ Historical Photos of Fruita & Western Colorado (Facebook) at https://www.facebook.com/HistoricalFruitaPhotos/posts/uintah-hotel-dragon-utahthe-uintah-hotel-served-barber-asphalt-paving-company-ex/710632196031675/

- “The Uintah Railway,” by William L. Chenoweth, 1985 abstract, Utah Geological Association at https://archives.datapages.com/data/uga/data/055/055001/17_ugs550017.htm

- “The Uintah Railway,” by Linwood W. Moody, The Railway and Locomotive Historical Society Bulletin, JSTOR at https://www.jstor.org/stable/43519884

- “The Uintah Railway,” by W. L. Rader. The Colorado Magazine, May 1935, at https://www.historycolorado.org/sites/default/files/media/document/2018/ColoradoMagazine_v12n3_May1935.pdf

- “Uintah Railway,” Wikipedia.org at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uintah_Railway

- “The Uintah Railway — Mack, CO to Watson, UT,” at https://www.abandonedrails.com/uintah-railway

- “What is Gilsonite,” TDM, at https://gilsonite-bitumen.com/en/products/what-is-gilsonite

Gosh, Jack, your notes/history/related facts on these images are fantastic. My dad had his own paving construction company in Portland Oregon. I know all the terms for asphalt, bitumen, but had never heard of gilsonite. Fascinating stuff.

Hi Carolyn, Thank you so much for your feedback. It’s so interesting to know your Dad had a paving construction company in Portland. Thank you for sharing!

-Jack