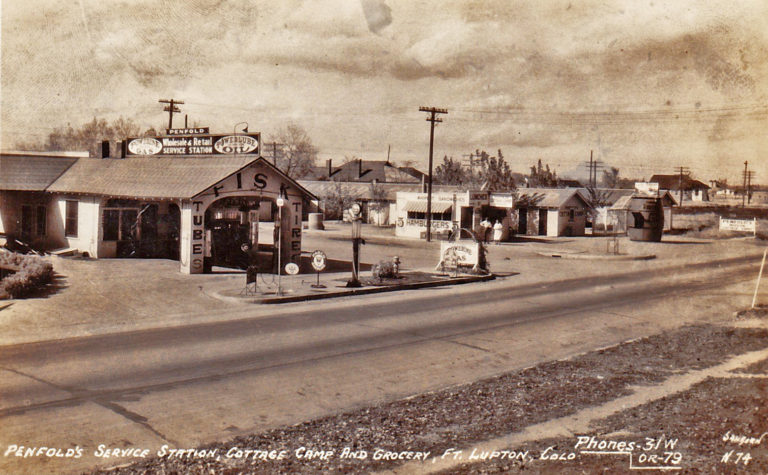

This photo views J.S and Edith Penfold’s businesses from the north as old Highway 85 becomes Denver Avenue. The sign in the foreground indicates they had a Willys-Knight Overland car dealership in addition to their other businesses.

It looks like someone is leaning into the open door of the car parked on the left. The sign just to the left of the car indicates there was a Sinclair gas station on the northeast corner of 9th and Denver, an apparent competitor with the Powerine gas sold by the Penfolds.

Fort Lupton had its water tower by this time. You can see it peeking over the roof of the house next to the Penfold gas station.

The sender of this postcard wrote to Alda Jones in Sheridan, WY: “Dear Mother: Arrived here at 5 this morning & so tired we had to go to bed. Ft. L. is just a few miles from Den. Have had fair luck so far. We plan on getting into C.N.M. some time Sun. Write to me right away. Lots of love, Babe”

Note the reference at the bottom of the picture to the “paved Lincoln Highway.” If you’d like to read about that highway, see the section below.

A Detour onto the Lincoln Highway

This highway did not pass through Lupton, as indicated in the photo, but there is an interesting story behind it. The Lincoln Highway stretched from New York City to San Francisco, and its creator was Carl G. Fisher, a race car driver, manufacturer of Prest-O-Lite compressed carbide-gas headlights for cars and builder of the Indianapolis Speedway. In 1912, Fisher had recognized that there were few good roads in the United States. Most of the two-million-plus miles of road then in existence were dirt, spreading out from individual towns and settlements but coming up short by way of connecting those places. It was easier to take the train.

Fisher called his idea the “Coast-to-Coast Rock Highway,” a graveled road that would cost about ten million dollars, with communities along the route providing equipment in return for free materials and the chance to be on the country’s first transcontinental highway. The highway would be named after President Lincoln.

Fisher’s goal was to raise the needed funds through donations, and his enthusiasm drew a group of automobile enthusiasts and industry officials who would form the Lincoln Highway Administration (LHA). The president of the LHA was Henry Joy, head of the Packard Motor Car Company, and Fisher was the vice-president. The plan was for the highway to be finished in time for the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco.

To raise money, Fisher and the LHA relied heavily on publicity, which included media events and announcements of donations from well-known people, such as Teddy Roosevelt and Thomas Edison. In 1913, in an effort to ascertain the final route which this highway would take, Fisher joined members of the Indiana Automobile Manufacturers association on a trip dubbed the “Hoosier Tour.” This tour included a number of states, including Colorado and Kansas, and, and Fisher’s intent while on the tour was to distinguish the tour route from what would become the route for the Lincoln Highway. But while on that tour, he all but promised the governors of Colorado and Kansas that the Lincoln Highway would pass through their states. Thus, when the route of the Lincoln Highway was finally announced by Henry Joy at the 1913 conference of governors in Colorado Springs, it was with great disappointment that the governors of Colorado and Kansas learned their states would not be on it Here’s a link showing the route of the Lincoln Highway: https://www.lincolnhighwayassoc.org/.

It’s interesting to note that a key factor behind the LHA’s exclusion of Colorado from the Lincoln Highway route were the mountain grades drivers would encounter there. If the Lincoln Highway had been routed through Colorado, it reportedly would have traversed Berthoud pass, but Henry Joy, wanting as level a route as possible, determined that Wyoming would prove more advantageous in this regard. One source I came across pointed out that “Wyoming offered a relatively easy grade that reached 8,835 feet, whereas the climb over Berthoud Pass reached 11, 314 feet.”

Back then, cars did not have fuel pumps, so drivers not only had to think about how much power their engines had, but also whether they could keep gasoline flowing to the carburetor. They had to depend on gravity, or the combination of gravity and the vacuum created by the car’s engine, to deliver the gasoline. In speaking to this subject, I’m very fortunate to know fellow former Luptonite David Haddock, who has an exceptional knowledge of cars. He owns, drives and maintains a beautiful 1928 Chevrolet National 4-door sedan and a 1951 Chevrolet convertible that belonged to his father.

To quote from an e-mail David sent me:

“The early cars did not have fuel pumps but relied solely on gravity or a combination of gravity and the vacuum created by the engine to suck fuel from the gas tanks. Which method was used depended on the auto maker. For many Model Ts and the Model A, Henry Ford preferred to mount fuel tanks in front of the dashboard and used gravity alone to move the fuel to the carburetor.”

“Somewhere along the line someone, probably with a racing background like Louis Chevrolet, decided that carrying 10 or 12 gallons of very flammable fuel in your lap could be a little dangerous! Some automakers, including Chevrolet, decided to mount the fuel tanks in the rear of the car safely within the car frame, between the back seat and the rear bumper. This required using the vacuum principle to ‘suck’ the fuel from the tank. To make this work effectively they mounted a small, one-half gallon or so, tank in the engine compartment above the carburetor. This tank was fitted with a float system so it would use the engine vacuum to pull from the regular fuel tank to keep it full and dispense gas into the carburetor via gravity.”

Given the means for fuel delivery described above, the challenge back then for a driver on a steep uphill grade was to avoid going beyond the point when the angle of incline would overwhelm a gravity or vacuum/gravity fuel delivery system. A successful attempt for the summit thus might require the driver to make a timely stop, turn the car around and continue the climb in reverse! David witnessed this several years ago (in the days before his 1928 Chevrolet) when he accompanied an auto touring group to the Jackson Hole/Tetons area. He said that, in order to climb the pass from Jackson Hole into Idaho, a number of drivers in cars of older vintage had to reach the summit while in reverse. He said it was a comical sight to see these cars crawling along at 10 mph or less in the breakdown lane.

Colorado would raise enough of a ruckus about not being included on the Lincoln Highway that the LHA agreed to the addition of a Colorado “loop.” It would branch off the Lincoln Highway at Big Springs, Nebraska, and run a southwesterly course, passing through or near the towns of Julesburg, Ovid, Sedgwick, Crook, Iliff, Sterling, Atwood, Merino, Hillrose and Camden. When it hit Brush, it turned due west and ran through Fort Morgan, then turned due south at Wiggins, where it stair-stepped its way south and west through Bennett and Watkins, entering Denver from the east on what is now Colfax Avenue. In Denver it ran west on what may now be Highway 36 and then hooked due north on what is now Highway 287 all the way to Cheyenne, where it would rejoin the original Lincoln Highway. To the dismay of Coloradans, though, the LHA would withdraw its recognition of the “loop” in 1915.

It would be a mistake to think of the Lincoln Highway as a uniformly constructed, cruising highway, for long distance travel by car was a different ball of wax back then. Even the LHA’s own Official Road Guide for 1916 referred to a road trip from the Pacific to the Atlantic on the Lincoln Highway as “something of a sporting proposition.” At a time when the current-day service infrastructure for cars was a long way off, one piece of advice from the guide stood out for me: Meant to reassure motorists approaching Fish Springs, Utah, the guide said, “If trouble is experienced, build a sagebrush fire. Mr. Thomas will come with a team. He can see you 20 miles off.” Other recommendations from the LHA Guide included buying gasoline at every opportunity, even if you had just purchased some a few miles back; wading through water before fording it in order to assess its depth; traveling with a set of tools, chains, a shovel, ax, tire casings, and innertubes; and, given the great likelihood of encountering mud, not wearing new shoes. (Here’s a link to a photo of a driver in the mud on the Lincoln Highway near Tama, Iowa, in 1913: https://www.lincolnhighwayassoc.org/history/car_in_mud_tama_1000.jpg)

Last but not least, we circle back to the reference in the postcard photo to the “paved Lincoln Highway” as it entered Fort Lupton from the north on Denver Avenue. After researching this, I learned that this was not part of the Lincoln Highway and was thus reminded that you can’t always believe what you read. This use of the Lincoln Highway name was evidence of an effort, not sanctioned by the LHA, on the part of Greeley and other area towns to get in on the Lincoln Highway bandwagon. Known by some as the “Greeley Branch,” it came off the Colorado “loop” at Fort Morgan, ran over to Greeley in a west/northwest fashion and from there ran south to Denver on what was later known as old Highway 85.

REFERENCES:

- “A Brief History of the Lincoln highway” at https://www.lincolnhighwayassoc.org/history/

- “Day 6: June 13, 2014, Hang On Loopy” Denny Gibson blog at http://www.dennygibson.com/lhconf14/day06/

- E-mail communications with David Haddock

- “ Greetings from the Lincoln Highway: A Road Trip Celebration of America’s First Coast-to-Coast Highway,” by Brian Butko, at:

- “The Lincoln Highway,” by Richard F. Weingroff, Highway History, Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Dept of Transportation at https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/lincoln.cfm

- “Lincoln Highway in Colorado” at http://theplaygroundtrail.com/Playground/The_Lincoln_Highway.html

- “The Lincoln Highway Road Trip Guide,” by The Drivin’ & Vibin’ Team at https://drivinvibin.com/2021/07/06/lincoln-highway-road-trip-guide/

- “Major Innovations in Fuel Pump Design Since 1900,” GMB at https://gmb.net/about/