At 5:30 a.m. Sunday, August 1, 1920, more than 1,100 Denver Tramway Company employees, members of Local 746 of the Amalgamated Association of Street and Railway Employees of America, voted 887 to 11 to strike for higher pay. They had seen their wages eroded by the high inflation brought about during World War I, and were demanding a wage increase to 75 cents per hour over the maximum hourly rate of 58 cents they had been receiving. The year before, the War Labor Board had eliminated wartime restrictions, giving workers an 8-hour day and a wage hike. However, the Denver Tramway Company violated the board’s orders and cut wages instead. This led to a four-day strike in 1919. In July of 1920, the company again threatened to cut wages unless the City of Denver increased fares. However, the city, responding to public pressure against a fare increase, would not allow an increase, and the strike was on. The Denver Tramway Company responded to the strike with a statement that “two professional labor agitators inflamed the men with bitter speeches and won a strike vote” and reassured its customers that “experienced trainmen in large numbers from other cities are now en route to Denver to operate the cars.”

The Denver Tramway Company’s headquarters building, built in 1912, sat at 1100 14th Street. Attached to it was a three-story car barn, with additional car barns located on South Broadway and in east Denver.

The company, aware of the coming strike, had already arranged for John “Blackjack” Jerome, a successful strikebreaker, to assist them if there was a strike. He would go on to lead hundreds of strikebreakers in the Denver strike. This did not portend well for a peaceful resolution, for Jerome’s strikebreakers were not known for ending strikes through hugs and handshakes. Jerome telegraphed Denver Tramway Company officials five days before the strike, saying: “Am leaving this P.M. for Denver. In case of strike will break it for you.” Within minutes of the strike being announced, Jerome telegraphed and telephoned strikebreakers, some of whom he held ready in San Francisco and Los Angeles.

[Jerome, who was born Yiannis Petrolekas, emigrated from Greece to the United States in 1905. Industrious, he learned to speak English while working a series of jobs, including scrubbing pots and pans. In San Francisco, he got a job working for a tramway company, where he gained experience that would later prove invaluable. With a knack for business, in 1913 he obtained the backing of six investors and founded the San Francisco-Oakland Aerial Ferry Company, which offered short-distance plane trips in the San Francisco area. That same year, he changed his name to John Jerome and founded the Jerome Detective Agency. Having learned in the tramway business of the enduring conflicts between tramway owners and powerful unions, he utilized his detective agency for organizing sabotage against unions. He would hire hundreds of students and unemployed men looking for a day’s wage to break picket lines and made millions in this line of work. He acquired the personal handle “Blackjack” for the club he carried into strike-breaking confrontations.].

On Monday, August 2nd, approximately 100,000 people were forced to find alternate transportation. On Tuesday, the 3rd, the tramway company, still deadlocked in its talks with the union, announced it would utilize fifty strikebreakers to attempt to operate street cars that afternoon and expected to have two hundred strikebreakers on the job by Thursday morning. At the time of this announcement, the company reported that fifty-one of its cars had been covered with heavy wire screens to prevent damage “in case strikers attempt any disorder.” Meanwhile, the union continued a stance of “watchful waiting,” maintaining picketers at the tramways’ four division points. It was reported that hundreds of idle carmen had gathered in the areas of the picketing.

True to its word, at 3:10 p.m. on the 3rd, the tramway company oversaw the operation of the first streetcar on Denver’s streets since the strike’s inception on Sunday morning. The purpose was not to carry customers but to test the waters, for the car held twenty armed strikebreakers and tramway general manager Frederick Hild, and was piloted by none other than John “Blackjack” Jerome. Following the streetcar were four carloads of police, including chief of police Hamilton Armstrong and Frank Downer, city manager for safety and excise.

As that first car left the barn, strikers and other citizens let fly with cat calls, jeers and even cheers. The only notable incidents encountered were an attempt to put a switch out of commission and the attempted blockade of the police cars by the operator of a “jitney” bus. (The term “jitney” applies to a vehicle utilized for an informal, unlicensed taxi operation.) The “jitney” operator was arrested.

Wednesday, August 4th,would witness the tramway company’s operation of three street cars in the above manner and for the same purpose. Several times that day, the strikebreaker crews encountered crowds attempting to block their way, but reportedly were successful in dispersing them with a spray of carbonic acid and soap suds. When sprayed on the first crowd they encountered, one striker yelled “tear gas,” which greatly increased the speed of dispersal. That day witnessed at least 20 arrests for “investigation.” It was noted by tramway officials that many switches had been wrecked and would need to be repaired before the return of regular operation.

Violence

Thursday, August 5th, began peacefully but would end in bedlam. That morning, two thousand labor sympathizers paraded in downtown Denver, and labor leaders met with Denver mayor Dewey C. Bailey, who agreed to consider an arbitration plan put forth by Charles A. Ahlstrom, president of the Denver Trades and Labor Assembly. Around 5:00 p.m. that evening, Ahlstrom spoke to the gathered crowd, imploring them to avoid falling “into the trap set by the tramway company. They want you to start violence, but don’t do what they want you to.” His advice went unheeded. The crowd attacked the most recently arrived group of Jerome’s strikebreakers with rocks and bricks, breaking one’s jaw and gashing another’s head.

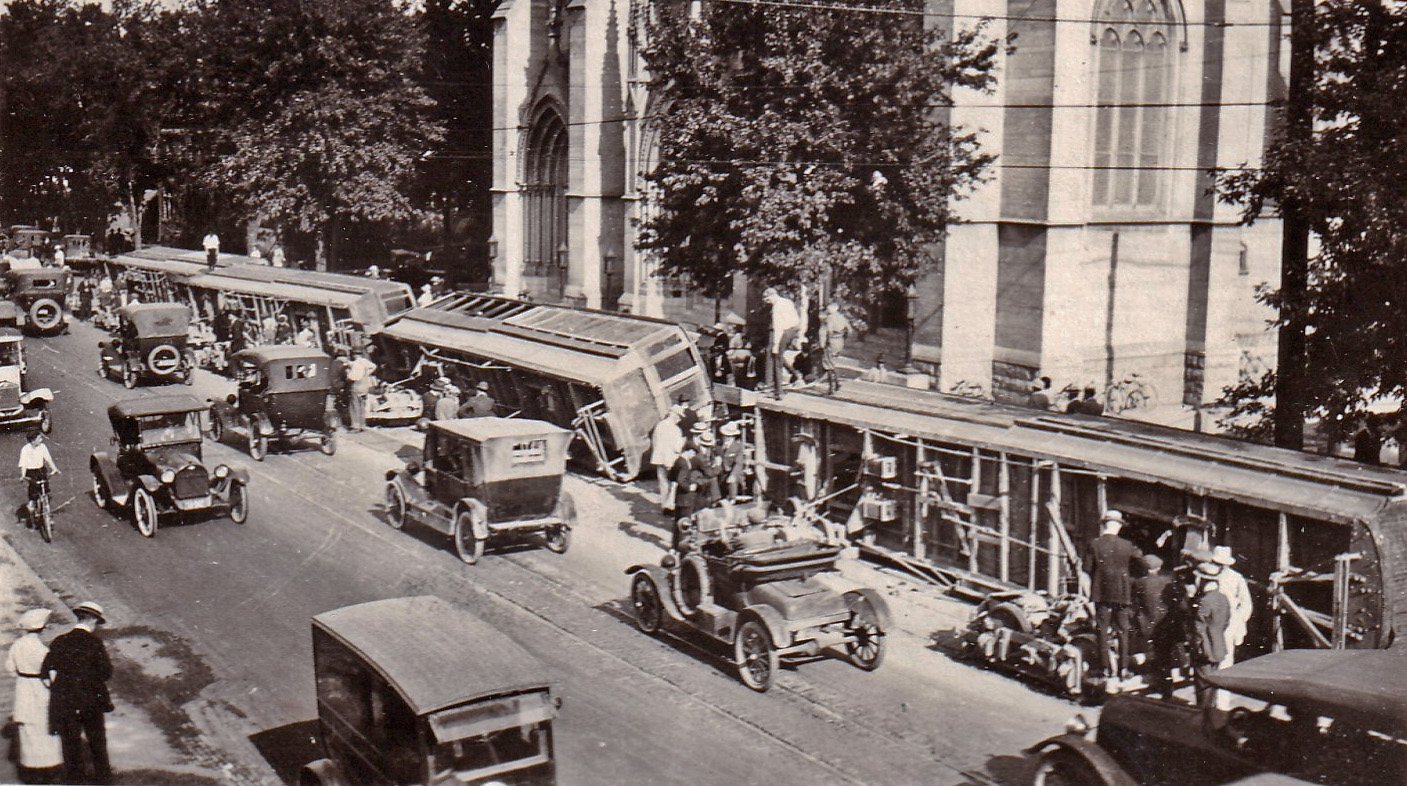

A large group of pro-labor marchers comprising streetcar employees, railroad employees, cigar makers, and other union supporters surged through downtown and formed into several mobs, which grew in size. At the intersection of Fifteenth and California, a mob spied two street cars blocked on the tracks by a stalled truck. They lit into the two cars, tearing off the recently installed protective screening. Within a few minutes, seventeen men had been seriously injured and the cars virtually demolished. The mobs clashed with police and strikebreakers all evening, and injuries continued to mount. As thousands of onlookers watched, rioting strikers and sympathizers attacked the strike breakers, throwing stones at them and wielding revolvers and clubs.

That evening, rioters overturned five tramway cars on Colfax Avenue in front of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, which resulted in the photo posted above. It is interesting to note that, with the intervention of its priests, the Cathedral provided safe shelter to a group of Jerome’s strikebreakers who had been chased there. A crowd of 5,000 outside the church pelted it with bricks and stones.

At around 9:00 p.m., a man named Ingraham, one of the 126 strikebreakers stationed at the tramway’s car barns on South Broadway, reported that the barns were being pelted by stones. An hour later, a Jerome henchman named Mullen was of the opinion that the crowd should be attacked. About fifteen minutes later, the rioters doused a fence with gasoline and set it afire. By this time, Jerome had arrived at the scene and, along with other strikebreakers, began shooting at the rioters, killing John Blade and A. G. Smith, both 19 years old, and severely wounding several others.

At 9:30 p.m., a mob of some 500 people, angered by the Denver Post newspaper’s support for the Denver Tramway Company, stormed into the Denver Post’s building on Champa Street, smashing windows and rampaging through its offices. Using crowbars and hammers, the marauders attempted to disable the presses, and they used gasoline-soaked rags to attempt to ignite piles of newsprint. Most of the damage proved superficial, however, and the Post was back in business within eighteen hours.

In the early hours of August 6th, two abandoned streetcars were set on fire. All told, six hours of rioting on the evening of August 5th, and into the early hours of August 6th resulted in two deaths and 39 injuries.

At some point, Denver mayor Dewey C. Bailey called for two thousand volunteers to assist the police in controlling the rioting, and as many as two hundred answered Bailey’s call. The volunteers’ armaments included two machine guns mounted on trucks and two sawed-off shotguns. Those operating private vehicles to substitute for street cars were having their tires shot out by strikers.

The evening of August 6th saw more bloodshed. At around 9:00 p.m., a touring car with some of Jerome’s strikebreakers arrived at one of the car barns to reinforce the men already stationed there. The crowd attacked the new arrivals, throwing bottles and bricks at the car’s occupants and causing serious injury to the chest of one of the strikebreakers. In response, Jerome’s men opened fire on the crowd, killing five and wounding eleven, the latter group including women and children.

Order Restored

On August 7th, 200 Army troops from Fort Logan arrived in Denver to restore order, under the command of Colonel C. C. Ballou. They were responding to a proclamation from Mayor Bailey turning over control of the city to the military. These troops would be supplemented by 500 Army troops from the U.S. Army’s Seventieth Division out of Fort Funston in Kansas requested by Colorado governor Oliver H. Shoup. Governor Shoup said in his telegram to the U.S. Army, “Riot situation following streetcar strike in Denver is beyond control of city and state authorities.”

With the arrival of the military, the violence was quelled almost immediately. The strikebreakers (and, I assume, those who volunteered to help fight the strike) were required to put up their weapons. On August 9th, Colonel Ballou’s commander, Major General Leonard Wood, arrived to assess the situation. He later said that the allowing the arming of Jerome’s strikebreakers was “a colossal blunder”.

Union members voted in a meeting held on the 7th to call off the strike if the Tramway Company would permit them to return to work in a body and send the strikebreakers out of town. After their meeting, union president Henry Silburg lamented the bloodshed, stating, “You do not know what the shooting, this loss of life, has done for me. I am a different man. I would do anything to end this bloodshed.”

Outcome

Aside from those who came through the ordeal alive and relatively unscathed and could say the same for loved ones, nobody won. The company was forced into receivership, with more than 700 employees losing their jobs. The building that held the Denver Tramway Company offices still stands at 1100 14th Street and is now the home of Hotel Teatro. It reportedly shows scars from the strike in the form of bullet holes.

REFERENCES:

- “Colfax History: Denver Tramway Strike” at https://www.colfaxavenue.org/2013/03/denver-tramway-strike.html

- “Colorado History: Denver’s deadliest riots happened during 1920 tram worker strike, YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YlUDJYuWiCg

- “Denver Cars to Start Running This Afternoon,” Fort Collins Courier dated August 3, 1920, Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection at https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=FCC19200803.2.6&srpos=23&e=——-en-20–21–img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA-denver+street+car+strike+——-0——

- “Denver streetcar strike of 1920,” Wikipedia at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Denver_streetcar_strike_of_1920#

- “Denver Tramway Company building, newly built as its headquarters in 1912.” Wikipedia at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Denver_streetcar_strike_of_1920#/media/File:TRAMWAY_BUILDING_(Teatro_Hotel)-1100_14th_Street.JPG

- “Denver Tramway Strike of 1920,” Colorado Encyclopedia, History Colorado at https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/denver-tramway-strike-1920

- “Dewey C. Bailey,” Wikipedia at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dewey_C._Bailey

- “Law-and-Order Resumes Sway,” The Colorado Statesman dated August 7, 1920, www.newspapers.com at https://www.newspapers.com/image/886476882/?match=1&terms=denver%20tramway%20strike

- “Oliver Henry Shoup,” Wikipedia at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oliver_Henry_Shoup

- “Queen City Tram-less,” The Norwood (San Miguel County) Post dated August 6, 1920, Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection at https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=NRP19200806-01.2.18&srpos=3&e=-08-1920–08-1920–en-20–1–img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA-denver+tramway+strike——-0——

- “Remembering Denver’s deadliest riots a century later,” by Cory Phare, July 31, 2020, RED, Colorado News and Culture from MSU Denver at https://red.msudenver.edu/2020/remembering-denvers-deadliest-riots-a-century-later/

- “Resurrecting the legend of John ‘Blackjack’ Jerome,” at https://www.ekathimerini.com/society/208233/resurrecting-the-legend-of-john-blackjack-jerome/

- “Strike Breakers on Three Street Cars in Denver,” The Greeley Daily Tribune dated August 4, 1920 NewspaperArchive at https://newspaperarchive.com/greeley-daily-tribune-aug-04-1920-p-1/

- “To the Public,” The Rocky Mountain News dated August 2, 1920, Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection at https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=RMD19200802-01.2.58.4&srpos=7&e=-08-1920–08-1920–en-20–1–img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA-denver+tramway+strike——-0——

- “Two Dead Result Riots in Denver Strike; Post Building is Dynamited” Montrose Daily Press dated August 6, 1920, Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection at https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=MDP19200806-01.2.13&srpos=22&e=——-en-20–21–img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA-denver+street+car+strike+——-0——

- “1920 Denver Street Car Riot Ends in Two Deaths, Partial Destruction of a Denver Post Building,” by Jess Brovsky-Eaker, Law Week Colorado dated July 15, 2022, at https://www.lawweekcolorado.com/article/1920-denver-street-car-riot-ends-in-two-deaths-partial-destruction-of-a-denver-post-building/

- “250 Federal Troops from Logan Rule Denver After Death List Rises to Five,” The Greeley Daily Tribune dated August 7, 1920, NewspaperArchive at https://newspaperarchive.com/greeley-daily-tribune-aug-07-1920-p-1/