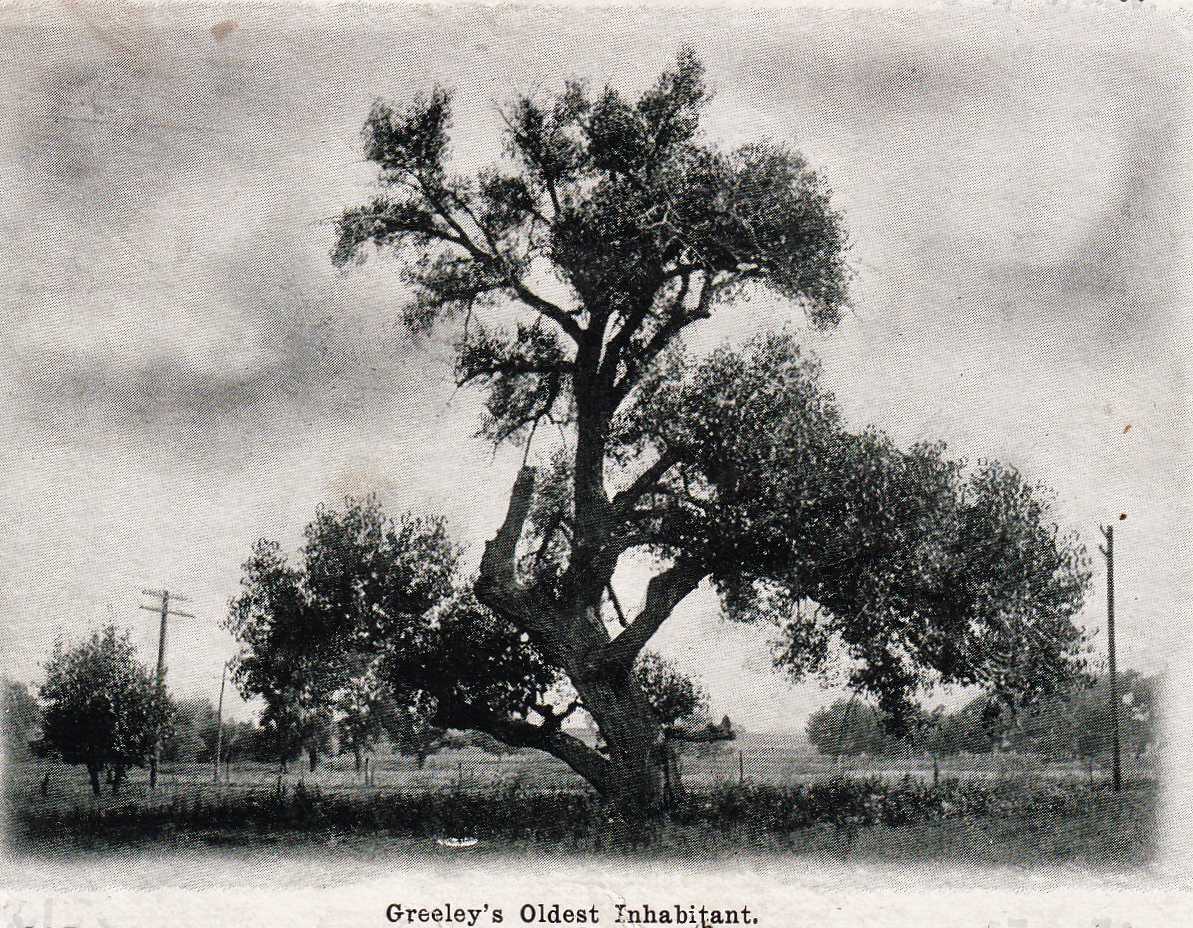

This picture appears on a postcard published by the Greeley Tribune in about 1905 and features the cottonwood tree that greeted the Greeley Union Colony setters when they arrived in 1870. Since it was there upon their arrival (it sat in what is now Greeley’s Island Grove Park), it became known as “Greeley’s oldest inhabitant.” When Nathan Meeker, an Ohioan and founder of the Colony, arrived with the others back then, he could not have foreseen that the saving of a young life at that tree several years earlier would redound to the benefit of his wife, Arvilla, and his daughter, Josephine, in a life and death situation.

The story of what happened at the tree involves a teenaged girl named Shawsheen of the Uncompahgre band of Utes and sister to Ouray, the band’s chief. In 1860 or 1861, Shawsheen, who was 15 or 16 at the time, was hunting with her family along either the Poudre River or in Big Thompson Canyon (accounts differ) when she was abducted by Arapahoes. Her family alerted the U.S. Calvary of this. It was later learned that the Arapahoes treated Shawsheen like a slave.

In 1863, a company of U.S. Cavalry stationed out of LaPorte (which sits six miles northwest of Fort Collins) and responding to reports of trouble between some settlers and an Indian raiding party, spotted “a young squaw tied to a tree,” around whom her Arapahoe captors were piling wood. The Calvary intervened and rescued her from what would have been a fiery death, and she was later safely re-united with her family. The “young squaw” was Shawsheen, and the tree is that which later became known as “Greeley’s oldest inhabitant.”

Jumping forward to 1878, President Hayes has just appointed Nathan Meeker Agent of the White River Ute Reservation, also known as the White River Agency, located on the Western slope in an area which currently incorporates the present-day town of Meeker. A primary mission of the reservation was to train Utes to become farmers. Meeker’s instrumental role in establishing the Greeley Union Colony, which was an agricultural enterprise, and his ties with Horace Greeley, owner, editor and publisher of the New York Tribune newspaper, were probably important factors in Hayes’ appointing him. Unfortunately, however, Meeker had no experience working with Indians and little knowledge of the Utes.

[Because of financial difficulties, Meeker had asked to be considered for the job. In 1870, he had borrowed $1,500 from Horace Greeley to establish the Greeley Tribune newspaper. When Greeley died suddenly in 1872, Meeker still owed him $1,000. Greeley’s daughters eventually sued him for that amount, and when 1878 rolled around, he still hadn’t paid it off.]

The White River Agency was responsible for about 900 Utes. Per the Ute Treaty of 1868, the Agency was to distribute rations and annuities (in the form of money or goods) to the Utes. However, due to negligence on the part of the government, these often arrived late or not at all. Thus, the Utes were greatly disinclined to pursue the agricultural goals of the Agency and chose to continue their traditional seasonal hunts, both on and off the reservation. Not surprisingly, perhaps, the government had been having a difficult time finding an agent.

Bureau of Indian Affairs policy at the time stipulated that, if adult Ute males on the White River reservation did not participate in agricultural activities, then food provided to them by the reservation would be withheld. This approach was not only cruel but unrealistic, being in direct conflict with the Utes’ centuries-old culture, which centered on horses and hunting forays, including seasonal bison hunting, but not farming.

When Meeker began his term as agent, the reservation was located in a high mountain valley. But Meeker, looking at the location solely from the perspective of farming, saw it as too high in altitude and too confining. He sought, and gained, approval from the U.S. government to move the agency down the White River about 20 miles to a larger, more open space. This space, however, was favored by the Utes for grazing and racing their horses.

Meeker brought a narrow-minded, arbitrary, and heavy-handed approach to his job as Agent. In a letter he wrote to Colorado U.S. Senator Henry Teller, who had endorsed Meeker for the position, he said, “I propose to cut every Indian down to the bare starvation point if he will not work.” Not surprisingly, given his attitude, tensions grew at the reservation following his appointment.

When Meeker made it known to the Utes that he considered horse racing a sin, this irritated “Doctor” Johnson, a White River Ute medicine man, who loved to race horses. Johnson unwisely decided to get back at Meeker by racing horses on a Sunday, which inflamed Meeker, who then ordered one of his employees, master farmer Shadrach Price, to plow up the Utes’ horse racing area. Price began doing so, but stopped after one of the Utes fired a gun over his head. This act induced Meeker to contact the U.S. Army to request that troops come in to enforce his rules. This was in the fall of 1879.

Fred Shepherd, another of Meeker’s employees, in a letter he had written to his mother, was probably referring to this incident when he wrote, “I don’t blame the Ute for not wanting his ground plowed up. It is a splendid place for ponies and there is better farming land…right west of this field, but it is covered in sage brush. Douglas (chief of the Nunpartca band of White River Utes) says he will have (the Utes) clear the sage brush if N.C. (Nathan Cook Meeker) will only let the grass alone. But N.C. is stubborn and won’t have it that way and wants the soldiers to carry out his plans. Don’t know how it will turn out, but you can bet if they (the Utes) touch anybody it will be the agent first.” Sometime after learning of Meeker’s request for troops, Utes shot and killed Meeker and his employees, including Price and Shepherd (Meeker’s employees numbered somewhere between seven and ten). The killers then fled, but not before capturing Meeker’s wife, Arvilla, his daughter, Josephine, Price’s wife and the two Price children.

The captives were taken to a camp beneath the rim of Grand Mesa on Mesa Creek. US interior secretary Carl Schurz had sent Charles Adams, a former Ute agent, to Colorado to find the captives, and he was able to do so with help from Ute guides and interpreters. He entered into negotiations with the Utes for the captives’ release. Instrumental in their release was Shawsheen, whom we met earlier in this story. She persuaded the Ute men to let the hostages go. All told, the hostages had been held for 23 days, with the women enduring taunting and threats.

I was surprised to learn of Shawsheen’s role in obtaining the release of the hostages. But It turns out that Shawsheen’s father, Guero, wanting to strengthen ties between the Uncompahgre and White River Utes, had arranged to have Shawsheen marry Canella, a White River Ute. Thus, it’s probable that Shawsheen was at the White River reservation at the time of the killings and knew the Meeker party.

For her role in gaining the release of the hostages, Shawsheen was hailed as a hero. Josephine Meeker, in writing about her ordeal, said, “we all owe our lives to the sister of Ouray (Shawsheen).” Today, there is a school in Greeley which carries her name – i.e., the Shawsheen Elementary School on West 7th Street.

Like the people in this story, “Greeley’s Oldest Inhabitant” is long gone. It was destroyed by a “terrific wind storm” on March 29, 1911.

I want to thank my brother, Jim, for this postcard.

REFERENCES:

- “Drive to Force Utes into Farming Led to Massacre,” July 4, 1976, The Daily Sentinel (Grand Junction), www.newspapers.com at https://www.newspapers.com/image/537232617/?terms=squaw%20susan&match=1

- “History Re-stitched: Shawsheen & Josephine Meeker,” City of Greeley Museums at https://greeleymuseums.com/history-re-stitched-shawsheen-josephine-meeker/ 1.001111

- “Horace Greeley, Wikipedia.com at https://www.google.com/search?q=horace+greeley+death&oq=horace+greeley+death&aqs=chrome..69i57j0i22i30j0i390.4012j1j15&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8

- “Hunter-gatherer,” Wikipedia.com at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hunter-gatherer

- “Laporte, Colorado,” Wikipedia.com at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laporte,_Colorado

- “The Last Major Indian Uprising, ” Rio Blanco County Historical Society at http://www.meekercolorado.com/HSociety.htm

- “Meeker Incident,” Colorado Encyclopedia at https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/meeker-incident#:~:text=In%20spring%201878%2C%20President%20Rutherford,editor%20arrived%20on%20the%20reservation.

- “Nathan Meeker,” Colorado Encyclopedia at https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/nathan-meeker

- “Nathan Meeker,” Wikipedia.com at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nathan_Meeker

- “Native American Data,” Genealogy Trails History Group at http://genealogytrails.com/colo/utereservation.html

- “Oldest Inhabitant in Greeley is Killed in Terrific Windstorm,” Greeley Tribune, March 30, 1911, Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection at https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=TGT19110330-01&e=——-en-20–1–img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA-greeley%27s+oldest+inhabitant——-0——

- “Ouray,” Colorado Encyclopedia https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/ouray

- “Reservation boundaries impose stationary agriculture on the Ute,” by Shawn Summers, Leadville Herald Democrat, dated October 7, 2020, at https://www.leadvilleherald.com/free_content/article_f17607c6-08ac-11eb-a3c7-f730c5f7f69e.html

- “Shawsheen,” Wikipedia.com at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shawsheen

- “Utes destined to be horse ranchers?,” by Tom Ross, Steamboat Pilot and Today, July 23, 2010, at https://www.steamboatpilot.com/news/tom-ross-utes-destined-to-be-horse-ranchers/

- “White River Ute Commission investigation. Letter from the Secretary of the Interior, transmitting copy of evidence taken before White River Ute Commission,” University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons at https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6987&context=indianserialset

- “White River Ute Indian Agency,” by Steven G. Baker, Colorado Encyclopedia at https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/white-river-ute-indian-agency