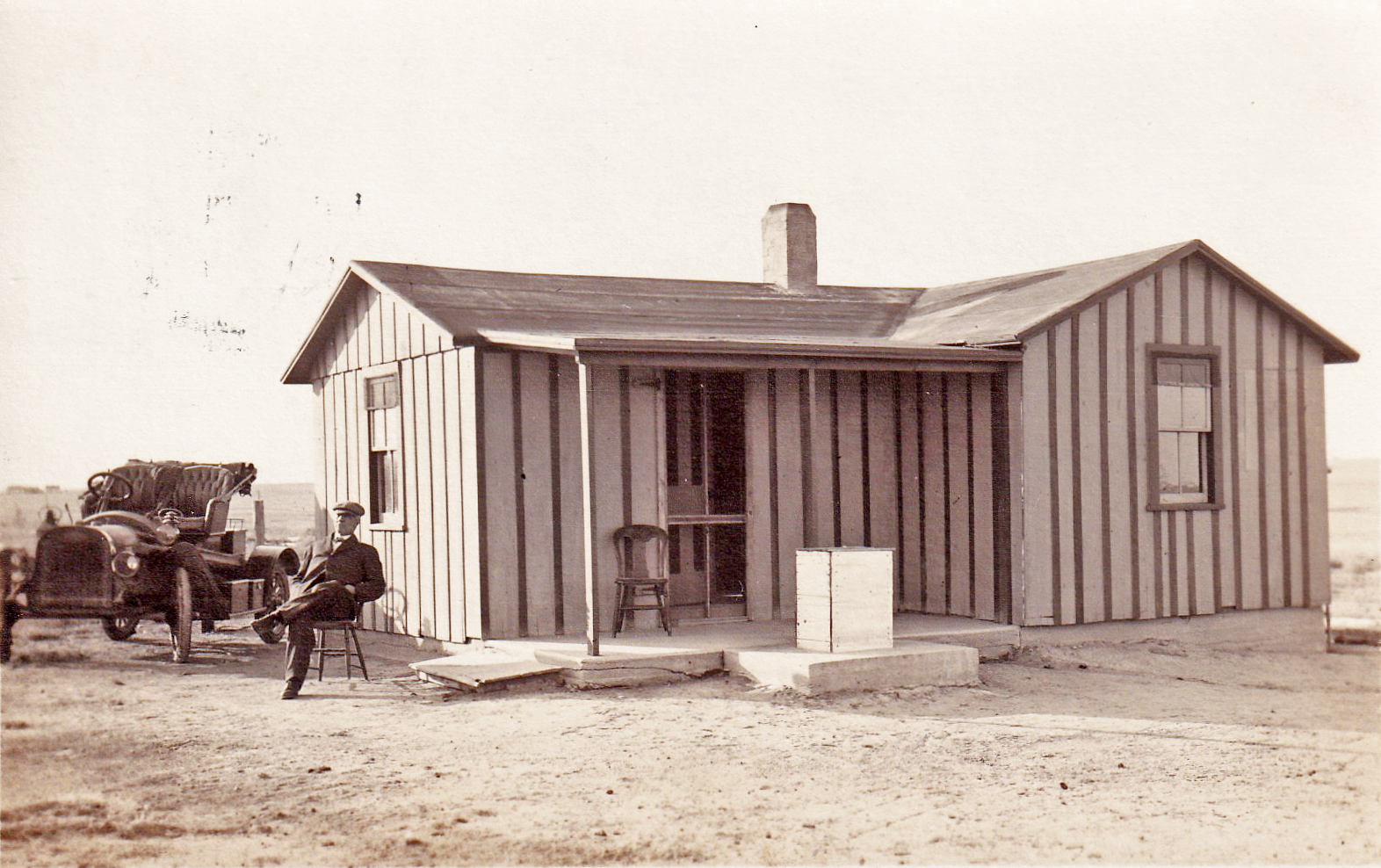

This postcard features a picture of the Randolph home in Brandon, Colorado. Originally it sat on the homestead claim of Olive Fitz Randolph. Olive is the sender of the card and is writing to Mrs. John Cummings in Olive’s hometown of Nortonville, Kansas. In her message dated March 13, 1914, she writes, “Dear Friend: This house used to be on my claim. Is now our home in Brandon. How are you? Best wishes, Olive Randolph.” (Olive’s house was moved to Brandon in the summer of 1913 by two individuals, identified by the Brandon Bell newspaper as G. N. Atkin and A. B. Randall. It would have been interesting to know how they moved it. I’m sure its small size was a plus.)

Located in the Big Sandy Valley in eastern Kiowa county, Brandon, a farming and ranching community founded in 1887, sits a little more than 20 miles west of the Colorado-Kansas border. It’s in Sand Creek country, about six miles east of the town of Chivington, named for the now infamous Colonel John F. Chivington, who at Sand Creek in late autumn of 1864 led calvary troops in a massacre of at least 150 native Cheyenne and Arapaho, most of them women, children and the elderly.

Brandon was once an important railroad town named by Jessie Mallory Thayor, the daughter of H.S. Thayer, who was the president of the Pueblo and State Line Railroad, later known as the Missouri Pacific Railroad. H.S. gave his daughter the task of naming the towns and sidings along his railroad line. The names she assigned were Arden (which was later moved to Sheridan Lake), Brandon, Chivington, Diston and Eads.

Brandon got off to a good start, in part because it was the mail distribution point for the towns of Water Valley and New Chicago (both now gone). However, its fortunes took a dive beginning with the closure of the post office in 1893. However, with people migrating into the area in 1907 and 1908 and the re-opening of the post office in 1908, Brandon made a new start. It was helped along by a man named Sanger, a promoter, who was responsible for the first land rush. The railroad of course helped the town thrive, bringing in settlers and supporting agricultural commerce. At one time it could boast its own bank, school, lumber company, hotel and restaurant. Now the town is virtually uninhabited, with a reported population of only 6 souls in 2021. (Brandon is an unincorporated town, meaning it doesn’t have a formal municipal government, which, among other things, can bring a certain order to town living. A wish for such order was expressed in a 1921 Brandon News newspaper article stating that, with Brandon’s incorporation, “the running of stock at large could be stopped and a nice toll exacted for each and every offense.”)

Olive Randolph, born February 17, 1885, was the sole child of Leslie Fitz “L. F.” Randolph and Adeline “Addie” R (Wheeler) Randolph. L.F. was born in 1851 in Pennsylvania, and Addie was born in Illinois in 1857. They were married in Kansas in 1883, and two years later Olive was born in or near the Kansas town of Nortonville.

L.F. and Addie both had ties to Kansas. In 1857, the same year Addie was born, she, her parents, her brother, Charley, and several other Seventh Day Baptist farming families moved from Illinois to form Seventh Day Lane, an agricultural colony outside of Nortonville. In 1863, L.F.’s parents, L.F. and his siblings left Pennsylvania and homesteaded in Kansas, most likely in Atchison County.

The claim Olive refers to in her postcard was filed under the Homestead Act, the same law that L.F.’s parents would have homesteaded under in Kansas in 1863. The Act was signed into law by President Lincoln on May 20, 1862, with the intent of stimulating Western migration. Under the provisions of the Act, after paying a small filing fee, a “homesteader” could claim 160 acres of land in the public domain. If, after five years, the homesteader could “prove up” — i.e., show continuous residence and/or development on that land — the homesteader would then own the land free and clear.

I initially believed the claim Olive referred to was the one I found on the U.S. Bureau of Land Management’s website at https://glorecords.blm.gov/details/patent/default.aspx?accession=253058&docClass=SER&sid=li4xabsk.qou . It shows that an Olive F. Randolph filed a claim through the Lamar, Colorado, land office on March 14, 1912. I was surprised, then, to come across a couple of newspaper articles from five years earlier, i.e., 1907, reporting Olive’s involvement with a land claim. One from the Nortonville News in March of that year reported that Olive and her father would be travelling to Colorado to “make further improvements on her claim there.” The other, published in December of that year in the Atchison (Kansas) Daily Globe. reported that Olive was “living on a claim near Sheridan Lake, Colorado.” (Sheridan Lake is about 8 miles east of Brandon.) Since Olive’s first claim predates her house being moved into Brandon by at least 6 years, well beyond the 5-year “proving up” period, it’s most likely that the house came from that first claim.

Olive’s father was an active, community-oriented man with a focus on newspapers and an abiding interest in real estate. As early as 1912, L.F. ran an ad in a real estate directory touting the Shallow Water Land Company, of which he was president. (The term “shallow water” is most likely a reference to land where the seasonal high groundwater table, also known as saturated soil, is less than three feet below the land’s surface.)

While in Kansas, L.F. was the editor and owner of the Nortonville News newspaper and sat on the board of directors of the Bank of Nortonville. In 1900, he was president of the Kansas state Editorial Association. It appears that, as early as 1906, he had relocated to Sheridan Lake, Colorado, where he would publish “The Colorado Farm and Ranch” newspaper. He went on to edit the Brandon Bell newspaper and was subsequently owner of The Westland, a Brandon newspaper formed out of three prior publications, the Brandon Bell, Farm and Ranch (Eads) and Midway Magazine. In 1912, L. F. held a Kiowa County court judgeship, and after that, it wasn’t unusual for him to be referred to as “Judge Randolph.”

Like her father, Olive left footprints in printer’s ink. At age 12, she was already doing the proof- reading for the Nortonville News, and as an adult was the Local Editor for The Westland. Olive also tried her hand at business. In 1920 she was the proprietor of the Brandon Bookshop. An ad for her shop in The Westland announced that her shop carried stationary, school and office supplies and notions. (The word notions normally was a reference to sewing-related items.)

It would be safe to say that L.F. played a big role in the doings of Brandon. In one Brandon News article he was referred to as “The Father of Brandon.” He was one of the founders of the Brandon Town Company, a shareholder-held business that had a part in platting the town and was most likely established to promote the town, make civic improvements as needed (e.g., in the early 1910’s the company put a deep water well into operation) and promote the sale of town real estate. At different times L.F. held the offices of President and Secretary with the company.

Perhaps it’s not surprising to see the photo of Olive’s home in its new setting in Brandon in 1914, for the Brandon Town Company placed ads in the local newspapers from at least 1913 to 1916 announcing the availability of town lots for sale. The promotion, however, may not have produced the desired results, for 1921 saw local ads placed by L.F. in the capacity of real estate agent announcing the sale of nearly a hundred town lots at “prices below actual value.”

January of 1917 saw the passing of Addie’s English-born mother, Maria Reynolds Wheeler, at age 94. A little over a year earlier, Addie had moved her mother to Brandon from her home at Nortonville. Addie’s father, Joshua, died in 1896. Following his death. Addie and her brother, Charley, looked after their mom, and in the eleven years preceding her mother’s death, Addie gave most of her time to caring for her. The need for Addie to be in Nortonville most of the time would have presented a challenge to the physical togetherness of the Randolph nuclear family. During that period, perhaps Olive and L.F. parceled their time in some fashion between their family home at Nortonville and their residential and work life in Colorado. I found two news articles that might speak to that. The first, an article from May 1906 in the Atchison (Kansas) Daily Globe, reported that Olive, who would have been 21 at the time, was traveling from Kansas to Sheridan Lake to keep house for her dad. The second article, this one from the 1907 Nortonville News and cited earlier, reported Olive and L.F.’s trip from Nortonville to Sheridan Lake to make improvements on Olive’s land claim. This would have been at a time when L.F. was publishing the Sheridan Lake newspaper. More than 400 miles separate Nortonville from the Sheridan Lake/Brandon area, so it wasn’t a quick trip. Given what was probably a greater availability of train service between towns back then, that distance may not have been too daunting.

About the photo: The man sitting regally on the chair is most likely Judge Randolph. The car looks pretty swanky, but I don’t know what kind it is. Any guesses? Note that the steering wheel is on the right side. Even though Americans have been required since 1792 to travel on the right side of the road, virtually all cars in the U.S. initially had right-hand steering. Ford began a trend away from this when it brought out the Model T in 1908. Ford’s thinking was that it was easier and safer for a passenger to exit on the side opposite oncoming traffic. Left-side steering in the U.S. didn’t became the standard, though, until the mid-1910’s.

Sadly, Olive died in 1925 at the age of 40. Her remains are interred in the Eads Cemetery in an unmarked grave. L.F. died in 1931 at age 80 at the Charles Maxwell Hospital in Lamar, and Addie lived until age 87, dying in Boulder in 1944. L.F.’s and Addie’s remains are also interred in the Eads Cemetery, and like Olive’s, rest in unmarked graves.

REFERENCES:

- Atchison Daily Champion, May 16, 1896, and February 1, 1888, at www.newspapers.com

- The Atchison Daily Globe, May 4, 1906, December 30, 1907, March 14, 1913, at www.newspapers.com

- Brandon Colorado Population 2021, World Population Review at https://worldpopulationreview.com/us-cities/brandon-co-population

- Brandon, Colorado, Wikipedia.org at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brandon,_Colorado

- The Brandon Bell, September 6 and October 25, 1912; August 22, 1913; October 16, 1914, Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection at https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org

- The Brandon News, January 27, August 4, August 24, September 1, October 27, and December 22, 1921, Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection at https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org

- Colorado Farm & Ranch (Eads), July 10, 1914, and January 26, 1917, Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection at https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org

- Colorado Farm & Ranch (Sheridan Lake), February 7, 1913, July 10, 1914, and April 9, 1915, Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection at https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org

- Colorado Post Offices 1859 to 1989, by Bauer, Ozment and Willard, 1990, Colorado Railroad Museum

- Distances from point to point, at www.google.com

- “Fact: American Steering Wheels Haven’t Always Been on the Left,” by Laurence Brown, March 13, 2013, Lost in the Pond at http://www.lostinthepond.com/2013/03/fact-american-steering-wheels-havent.html#.YBLwGTFKiUk

- Find a Grave at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/43831810/leslie-fitz-randolph

- “General Land Office Records,” Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Department of the Interior at https://glorecords.blm.gov/details/patent/default.aspx?accession=253058&docClass=SER&sid=li4xabsk.qou

- Fort Collins Express-Courier, July 8, 1931, at www.newspapers.com

- “The Horrific Sand Creek Massacre Will Be Forgotten No More,” by Tony Horowitz, Smithsonian Magazine, December 2014 at https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/horrific-sand-creek-massacre-will-be-forgotten-no-more-180953403/

- Jackson’s Real Estate Directory, 1912-1913, by Jay M. Jackson at Google Books https://books.google.com/books?id=zEhCAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA82&lpg=PA82&dq=Shallow+Water+Land+Company+brandon+colorado&source=bl&ots=RUxV8NeVFW&sig=ACfU3U1OtNAuPFZ0z2qVezyRHEtx0M4Cqg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwii3YqAoszuAhUQ7J4KHQo7BUUQ6AEwA3oECAYQAg#v=onepage&q=Shallow%20Water%20Land%20Company%20brandon%20colorado&f=false

- Jordan Family Tree at www.ancestry.com

- Kiowa County Press, dated January 28, 1916, Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection at https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org

- “Homestead Act: Primary Documents in American History,” Library of Congress Research Guides at https://guides.loc.gov/homestead-act

- “Long Time Gone and the ABC’s of Kiowa County Railroad Towns,” by Priscilla Waggoner March 3, 2020, Kiowa County Independent at https://kiowacountyindependent.com/lifestyles/long-time-gone/1757-long-time-gone-and-the-abc-s-of-kiowa-county-railroad-towns

- The Nortonville Herald, August 12, 1898, at www.newspapers.com

- The Nortonville News, September 16 1898, March 15, 1907, and January 26, 1917, at www.newspapers.com

- “Shallow groundwater,” Minnesota Storm Water Manual at https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Shallow_groundwater#:~:text=Shallow%20groundwater%20is%20a%20condition,3%20feet%20from%20the%20surfa

- Smith County Journal (Smith Center, Kansas), July, 1899, and June 7, 1900, at www.newspapers.com

- “Unincorporated area,” Wikipedia.org at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unincorporated_area

- U.S. and International Marriage Records, 1560-1900 at www.ancestry.com

- The Westland, dated January 28 and December 21, 1916,; January 25 and May 31, 1917; August 21 and December 16, 1919; March 19, 1920; March 4, 1921 Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection at https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org