The 1912 Summer Carnival, held from August 27th to the 29th, would be the 20th such annual event for Colorado Springs. This summer tradition began in 1893 with a “sunflower parade,” nearly a mile in length, of flower-bedecked conveyances, including horse-drawn two- and four-wheeled carriages, “brakes, …. bicycle riders, ladies and gentlemen on horseback, a burro brigade and even dogs and goats.” [A “brake” was originally a large, four-wheeled carriage frame with no body used for breaking in young horses. (I’m not sure how “break” became “brake.”) Later, “brakes” were adapted for passengers, one example being the “shooting brake” used for hunting, outfitted with a front-facing seat for the driver and footman or gamekeeper, and longitudinal benches along the sides in back for the hunters, their dogs and game.]

In the 1890’s, town festivals in Colorado grew in popularity, often promoting agricultural themes. For example, the year 1895 in Colorado saw the celebration of Watermelon Day in Rocky Ford, Peach Day in Grand Junction, Apple Day in Canon City, Potato Bake Day in Greeley and Jack Rabbit Day in Lamar. By 1897, the Colorado Springs celebration included a rodeo, with troops from Fort Logan and the Colorado National Guard marching in parades and staging a mock battle.

Newspaper articles and ads for the upcoming 1912 carnival told of “masquerading at night, balls, beautiful decorations and music” and the following three events:

- Shan Kive

Roughly translated from the Ute language, “Shan Kive” means having a good time. It is said to have originally referred to victory celebrations held by the Utes long ago in what is now the Garden of the Gods , an old Native American camping ground.

In the years 1911 to 1913, a group of citizens of Colorado Springs, hoping to attract tourists to relieve a depressed local economy, staged a revival edition of “Shan Kive.” Thus, in 1912, 33 years following the banishment of the Southern Utes to reservation lands near Ignacio, Colorado, Sapiah, the southern Ute chief (called Buckskin Charley by Whites), Chipeta, the wife of Ute chief Ouray, and approximately 50 members of the Southern Ute tribe, were invited out for the Summer Carnival. As many as 7,000 people may have turned out to watch the Utes’ performance of their native dances. Following the 1913 Shan Kive, the Bureau of Indian Affairs would put a halt to the practice of bringing the Utes north for the event, deeming it to be an exploitative use of the Utes akin to a circus attraction.

- A decorated automobile parade

This would be the opening event of the 1912 carnival. The August 23rd issue of the Fort Collins Weekly Courier spoke of this planned event as a “Monster Exhibition of Power Machines” meant to be “the greatest convocation of power machines ever brought together in this country.” Silver cup trophies would be presented for: “largest state representation excepting Colorado; first and second best trimmed gasoline cars; best trimmed electric cars; and…the city in Colorado sending the greatest number of machines, excluding the Pikes Peak region towns.” The anticipated participation by out-of-staters was not wishful thinking, for the previous year’s parade had featured 72 entries from Oklahoma, as well as entries from Texas, Kansas, Missouri, Iowa, Illinois, Nebraska, Arkansas and Louisiana! (It’s interesting to note that, in 1912, Colorado Springs could boast 123 miles of streets, less than 3 miles of which were paved.)

- The start of a transcontinental balloon race

Except for the reported turnout of 7,000 people for the 1912 Shan Kive, I was surprised to find no follow-up articles about it or the automobile parade. But, fortunately, given the subject matter of this photo, I did find detailed reporting about the balloon race, and the remainder of this narrative concerns that event.

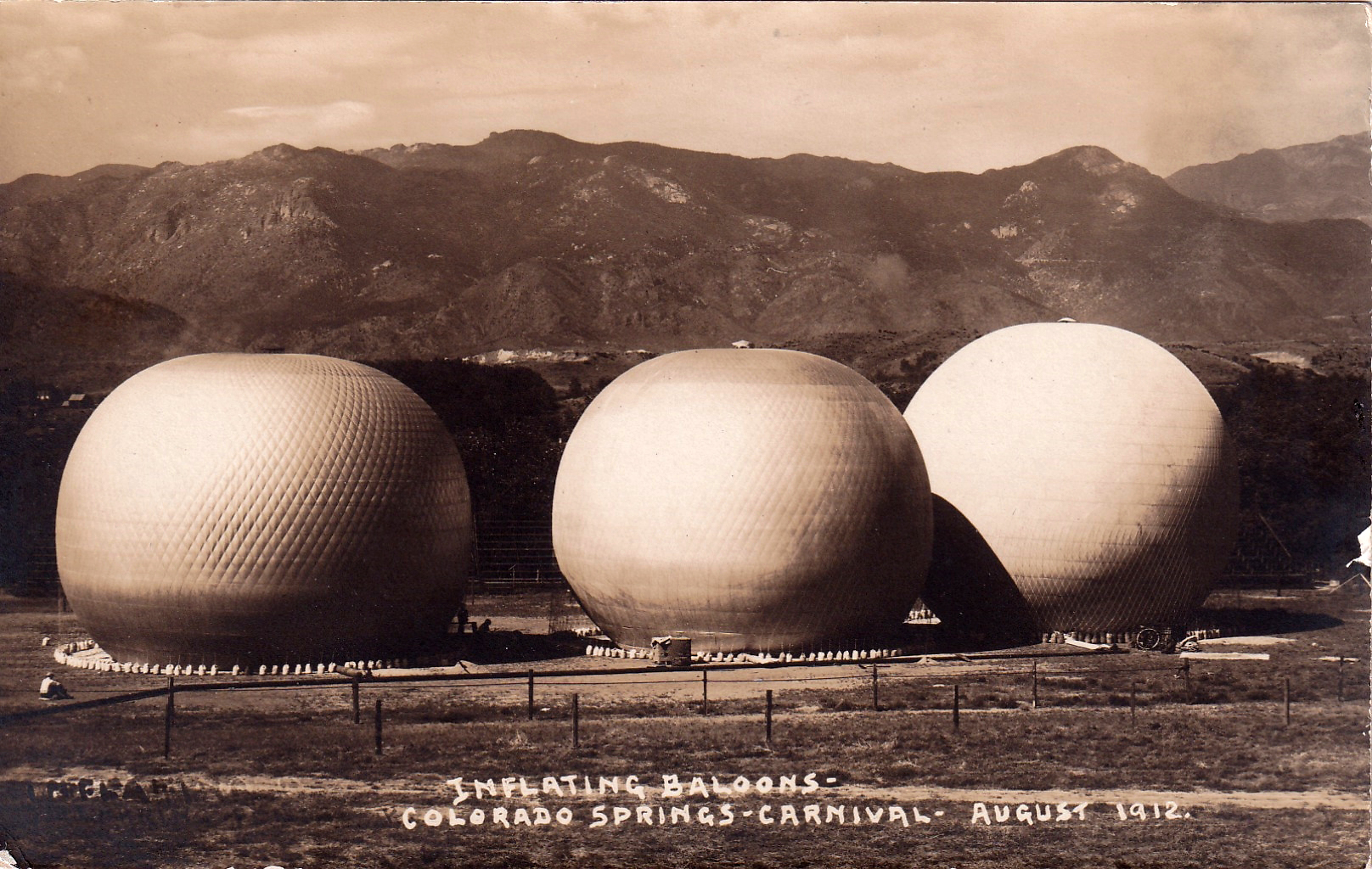

The photo of the three balloons was probably taken at their launch site, which was Washburn Field at Colorado College. They were most likely inflated with hydrogen or coal gas, the latter a mixture of hydrogen, methane and carbon dioxide produced by burning coal in a low-oxygen environment. The event was reportedly limited to just three balloons because of the “limited capacity of the local gas plant.”

Each of the balloons pictured held approximately 80,000 cubic feet of gas. Note the sand bags attached to the balloons to keep them on the ground, and, for a perspective on the size of the balloons, the man sitting at the far left. (It appears there are also a couple of people in the shadow of the left-most balloon.) The balloons’ sleek-looking envelopes, also called bags, may have been constructed of rubber-infused fabrics, such as those manufactured at the time by the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, or of rubberized silk, a material first developed in France in 1783 by brothers Anne-Jean and Nicolas-Louis Robert. The brothers created a varnish by dissolving rubber in a solution of turpentine, which they then applied to sheets of silk before stitching them together to create the bag.

The race was sanctioned by the American Aero Club of America and managed by Captain Harry E. Honeywell of St. Louis, who, it was said, had brought out for the race a group of “young society men from the Missouri cities.” They were also described in one newspaper account as “rich young men…who go into it for the fun.” Honeywell was a noted veteran balloonist from St. Louis who just the previous month had won the National Elimination Race out of Milwaukee, sailing his balloon for 35 hours and covering 925 miles before landing near the Civil War battlefield of Bull Run in Virginia. By winning that race, he would go on to compete internationally in Stuttgart Germany, where he would cover 1,260 miles and land near Moscow, Russia. During his lifetime he would make nearly 600 balloon flights and win three national tournaments, including the Kansas City race just mentioned. His title of Captain was an honorary one, perhaps based on his service in 1898 in the Spanish American war, during which he reportedly served with Admiral George Dewey in his defeat of the Spanish forces at Manila Bay in the Philippines.

The three pilots and their assistants were: Harry Honeywell, assisted by Bruce Gustin of Colorado Springs, in a balloon named “Uncle Sam;” John Watts (who had started out strong but lost to Honeywell in the previous month’s National Elimination Race) and his aide, Frank Blair, both from Kansas City, in the balloon “Kansas City II;” and Paul McCullough of St. Louis and his aide R.A.D. Preston of Akron flying a balloon named “X,” formerly named the “Goodyear.” (The Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company built its first balloon in 1912 and began building airships, or blimps, in 1917.) Unfortunately, I have no information indicating which of the pictured balloons is which.

The three crews shared the hope of establishing a new distance record of at least 1,200 miles, and pre-race optimism was high, with all three pilots rating the conditions as ideal for staying up a long time. Their optimism reflected that of the newspaper ads announcing the event as a “Transcontinental Balloon Race.” The balloons would lift off on the evening of August 28th in front of a crowd of approximately 20,000 people, including people perched atop rooftops and hillsides, with the “Kansas City II” lifting off at 5:45 p.m., the “Uncle Sam” at 5:58 p.m. and the “X” at 6:01 p.m. They would sail out of sight almost directly due north in a light wind.

The race was a bust, or, as one newspaper headline put it, a “fizzle.” Watts and Blair of the “Kansas City II” would be the “winners,” logging all of 49 miles to Sedalia; the “Uncle Sam” would touch down at Perry Park, located about 25 miles north of Colorado Springs; and the “X” would make it to Palmer Lake, 24 miles out. Despite the pilots’ earlier statements that conditions were ideal for sustained flight, their post-race assessment pointed to “contrary air current (sic) caused by the proximity to the Rocky Mountains” as the cause of their abbreviated flights, and “X” pilot MCullough also attributed his balloon’s early descension to “poor gas.”

REFERENCES:

- “Balloon Race for Springs” Montrose Daily Press dated August 6, 1912, Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection at https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=MDP19120806-01.2.58&srpos=20&e=–1893—1912–en-20–1–img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA-colorado+springs+balloon——-0——

- “Balloons Start Bravely but Soon Come to Earth,”The Herald Democrat dated August 29, 1912, Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection at https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=THD19120829-01.2.19&srpos=25&e=–1911—1913–en-20–21–img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA-colorado+springs+balloon——-0——

- “Big Balloon Race at Springs Is Fizzle,” The Telluride Journal dated September 5, 1912, Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection at https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=TTJ19120905.2.56&srpos=4&e=–1893—1912–en-20–1–img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA-colorado+springs+balloon——-0——

- “Brake (carriage),” Wikipedia.org at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brake_(carriage)#:~:text=A%20brake%20(French%3A%20break),their%20dogs%2C%20guns%20and%20game.

- “Bureau of Indian Affairs,” Wikipedia.org at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bureau_of_Indian_Affairs

- “A City Beautiful Dream: The 1912 Vision for Colorado Springs,” by Charles Mulford Robinson, 2020 at https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5550d8bde4b0b2b29270c299/t/55802920e4b0573c55925be3/1434462496894/a-city-beautiful-dream-the-1912-vision-for-colorado-springs.pdf

- “Colorado Springs Flower Carnival,” Florence Refiner dated August 13, 1897, Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection at https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=FRF18970813-01.2.37&srpos=8&e=–1893—1912–en-20–1–img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA-colorado+springs+festival——-0——

- “Distance Between Cities at https://www.distance-cities.com/distance-colorado-springs-co-to-sedalia-co , https://www.distance-cities.com/distance-colorado-springs-co-to-palmer-lake-co

- “Elimination Race in America,” The Mercury (Hobart, Tasmania) dated July 31, 1912, TROVE at https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/10238352

- “Explore the Blimp’s History,” Goodyear Blimp at https://www.goodyearblimp.com/relive-history/

- “Festival Days in Colorado,” The New Castle News dated June 22, 1895, Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection at https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=NCN18950622.2.72&srpos=17&e=–1893—1912–en-20–1–img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA-colorado+springs+festival——-0——

- Garden of the Gods, Wikipedia at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Garden_of_the_Gods

- “Great Auto Parade at Colorado Springs,” The Weekly Courier (Fort Collins) dated August 23, 1912, Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection at https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=TWC19120823.2.105&srpos=1&e=–1912—1912–en-20–1–img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA-carnival+auto+parade——-0——

- “Hot air balloon,” Wikipedia.org at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hot_air_balloon#:~:text=A%20hot%20air%20balloon%20is%20a%20lighter-than-air%20aircraft,an%20open%20flame%20caused%20by%20burning%20liquid%20propane.

- “Harry Honeywell, Balloonist, Dies,” the New York Times dated February 11, 1940, at https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1940/02/11/96927328.html?pageNumber=51

- “The Historical Garden of the Gods – Native American Crossroads” at https://sites.google.com/site/thehistoricalgardenofthegods/native-american-crossroads

- “Jacques Charles and the First Hydrogen Balloon,” November 12, 2021, SciHi Blog at http://scihi.org/jacques-charles-hydrogen-balloon/

- “Missing Balloon Lands,” The Springfield Herald dated September 6, 1912, Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection at https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=SPH19120906-01.2.47&srpos=22&e=–1893—1912–en-20–21–img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA-colorado+springs+balloon——-0——

- “Pike’s Peak Region “Shan Kive” & Summer Carnival,” The Rifle Telegram dated August 23, 1912, Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=TRT19120823-01.2.12.2&srpos=5&e=–1912—1912–en-20–1–img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA-carnival+auto+parade——-0——

- “Shan Kive,” by Suzy Lewis, July 26, 2018, Under the FAC at http://underthefac.blogspot.com/2018/07/shan-kive.html

- “Shan Kive Carnival Balloon Race Interesting,” Durango Semi-Weekly Herald dated August 29, 1912, Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection at https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=DSH19120829-01.2.11&srpos=8&e=–1893—1912–en-20–1–img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA-colorado+springs+balloon——-0——

- “Springs to Have Balloon Race at Summer Carnival,” The Telluride Journal dated August 1, 1912, Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection at https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=TTJ19120801.2.45&srpos=24&e=–1893—1912–en-20–21–img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA-colorado+springs+balloon——-0——

- “Springs Shan Kive Festival Short-Lived,” Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph dated August 9, 1987, at https://more.ppld.org/SpecialCollections/Index/ArticleOrders/296643.pdf

- “A Sunflower Parade,” Saguache Crescent dated September 14, 1893, Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection at https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=SGC18930914-01.2.5&srpos=2&e=–1893—1893–en-20–1–img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA-parade+colorado+springs——-0——

- The Windsor Beacon, dated July 18, 1912 (www.newspapers.com)

- “The World of 1898: The Spanish-American War,” Library of Congress at https://loc.gov/rr/hispanic/1898/dewey.html