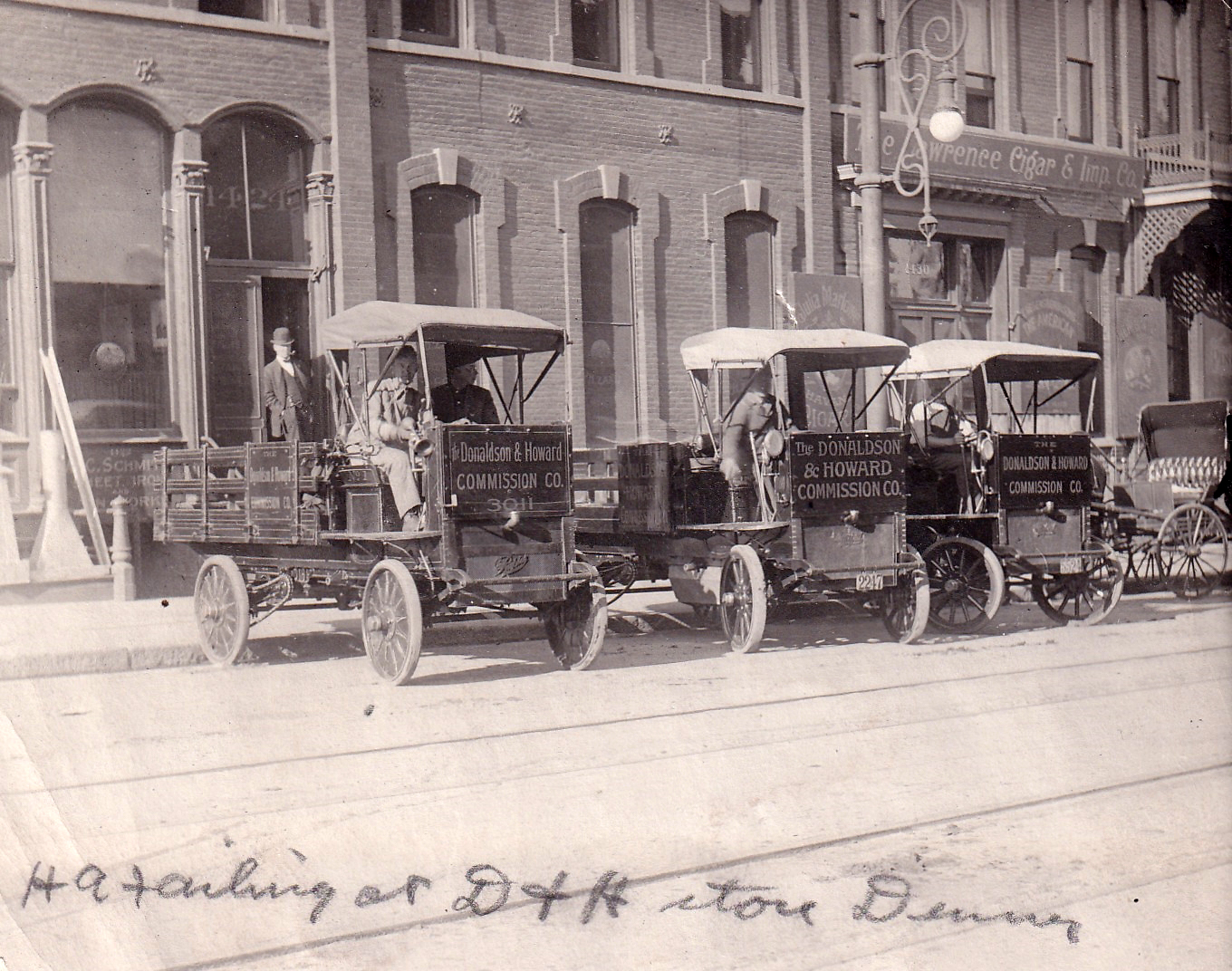

This photo shows the fleet of three Rapid trucks owned at that time by the Donaldson & Howard Wholesale Fruit Commission company. At the time this photo was taken, the company was located at 1612-18 Market Street in Denver. It was in business as early as 1894 and as of 1919 was still serving merchants in Colorado, Wyoming, New Mexico, Kansas and Nebraska.

The photo shown also appeared in an article by C. M. Smyth titled “Commercial Cars in Denver” in the January 1, 1912, edition of the “Cycle and Automotive Trade Journal.” Smyth bubbles with exuberance about the movement to motorized transport among Denver businesses and identifies Donaldson and Howard as a company leading a trend among wholesale businesses. He reports that the years 1909 through 1911 saw approximately 85 motor trucks brought into service by Denver businesses, a majority of them in the final six months of that period. Though probably not intended, this photo, dominated by the three motor trucks with the horse-drawn buggy barely squeezed in at the far right, would seem to symbolize the move toward mechanized transport.

The three Rapid trucks pictured here are equipped with Firestone hard rubber tires, which I imagine could have made for a pretty rough ride. The trucks are probably one ton in capacity. Note the steering wheels on the right side and the chain drives.

These trucks were manufactured by brothers Max and Morris Grabowsky, who founded the Grabowsky Motor Company in Detroit in 1900 and then reorganized in 1902 to form the Rapid Motor Vehicle Company in Pontiac, Michigan. In 1905, they built a 35,000 square feet truck assembly plant in Pontiac, the first plant in the world devoted to building commercial vehicles.

(To see a photo, circa 1909, of a Donaldson & Howard truck that was most likely acquired sometime after the three Rapid trucks discussed above, see my blog posting at Jacks Old Photos of Colorado.)

The “H.A. Failing” referred to in the caption at the bottom of the photos is probably Michigan native Henry A. Failing, who worked as a salesman for Donaldson & Howard for several years. Perhaps he’s the person standing in the doorway. Although the caption identifies Failing as being at the D&H store in Denver, none of the business signs or street numbers confirm that.

In 1908, William C. Durant, who would later co-found the General Motors Company, began buying up Rapid stock as well as interest in the Reliance and Randolph Truck Companies. He would combine these three companies into the General Motors Truck Company, later known as the General Motors Company (GMC). Thus, the Rapid truck was an ancestor of GMC trucks. I read a funny response to the “Just a Car Guy” blog which talked about the forming of GMC. The reader wrote: “After reading this whenever I see a GMC I will think Grabowsky Motor Co.”

A bragging point for the Rapid Truck Company was that one of their trucks was the first to conquer Pikes Peak. This took place on August 1, 1909, during that year’s Glidden Tour; this was the third year in a row in which a Rapid truck had participated in the tour.

The truck which topped the peak was a model F-406-B and carried five: two drivers, Rapid service manager James Carry and service department employee Frank Grogan, Rapid’s advertising manager, T.P. Myers, a photographer, and an unidentified fifth man. Here’s a photo link to the car and crew near the Pikes Peak summit that day: The truck which topped the peak was a model F-406-B and carried five: two drivers, Rapid service manager James Carry and service department employee Frank Grogan, Rapid’s advertising manager, T.P. Myers, a photographer, and an unidentified fifth man. Here’s a photo link to the car and crew near the Pikes Peak summit that day: EB01g338.jpg (750×504) (msu.edu). It reportedly required a day for the crew to make the climb. They sure look tired.

The Glidden Tours

The original Glidden tours were held in the years 1904 through 1913 by the American Automobile Association (AAA) to promote the public’s awareness and acceptance of motor vehicles. At the turn of the century, motor vehicles were viewed by much of the public as toys for the wealthy and of no apparent use for most people. Also, road conditions back then were not what they are now and did not exactly beckon one to experiment with this new type of machine.

The AAA tours were originally titled the “National Reliability Tours” but were renamed the “Glidden Tours” in honor of Boston millionaire Charles Glidden, who provided enthusiastic and steady support and financial assistance for these events. As the original title of the tours indicated, the goal of each tour was not to see who could cover the designated route in the shortest time, but to assess the reliability of vehicles when subjected to long-distance driving. Thus, the tours were more endurance contests than races.

The 1909 tour would commence in Detroit at Cadillac Square, near the Pontchartrain Hotel, on the morning of July 12, 1909, and would finish on July 30th in Kansas City, Missouri. Thus, with two two-day rest periods during the tour, the contestants were facing a total of 15 days of driving. The tour that year was about 1,000 miles longer than the 1908 tour, for a total of 2,636.5 miles.

The 1909 tour saw significantly stricter rules than the 1908 tour, with penalty points assigned for repair work performed, as assessed and recorded by an observer placed in each car. All entrants were required to provide a list of the tools and parts being carried, with an inspection of same at the end of the tour. On the positive side, the penalty point system was graduated, i.e., down to as little as a tenth of a point, to make the penalties proportionate to the nature of the repair.

Penalty points would also be levied for cars exceeding the day’s time limit. This limit was based on an assumed travelling speed of 20 miles per hour. Thus, if a particular day’s scheduled destination was 200 miles away, the contestants would have 10 hours in which to reach that destination. This meant that driver and crew, if running significantly behind in time on a particular day, might have to forego stopping for lunch or other needs.

AAA Contest Board Chairman Frank Hower stressed the following to the contestants: “The rules are much more exacting. The tour is not to be a wild flight across country, with cars being rebuilt, and no record made of their troubles. The cars will carry observers and travel so closely together that there will be no chance of anyone changing a bolt without it being known, to say nothing of putting in a new axle or spring.” His remarks indicate that there may have been some shenanigans in previous tours!

That year there would be three trophies awarded, by class of car, for best (i.e., lowest) score at the end of the tour: 1) The Glidden, for touring cars, i.e., those having “a regular touring chassis, mounted by a full touring body and carrying four passengers or equivalent ballast;” 2) The Hower, for runabouts, i.e., those having “a regular stock chassis, mounted by a runabout body carrying at least two people:” and 3) The Detroit, for those having “any stock chassis mounted by a miniature tonneau (rear passenger compartment) and carrying four persons, or the equivalent ballast.”

Quite a number of car makes were represented in the tour:

In the touring class were cars by Premier, Chalmers-Detroit, Marmon, E-M-F, Maxwell, Jewel, Pierce Arrow, Glide, Thomas, Midland, Stoddard-Dayton and White. The White distinguished itself by burning kerosene as fuel.

In the runabout class were cars by Moline, Brush, Chalmers-Detroit, Hupmobile, Maxwell, Pierce Arrow, McIntyre, Stoddard-Dayton, Jewel and Mason.

In the tonneau class were American-Simplex, Chalmers-Detroit and Premier.

Providing accommodations along the way for the two hundred or so drivers and crew was a challenge, especially given the small size of many of the communities hosting overnight stays. The solution arranged for by AAA, for at least a majority of the tour, was to have a train of six Pullman cars and three dining cars follow the tour, beginning with the stop in Fort Dodge, Iowa. After a night’s sleep in the Pullmans, the participants would head for the dining cars for breakfast, to return that evening for dinner. In addition, each would receive a box lunch.

Unfortunately, a good night’s sleep in a Pullman wasn’t always possible because of the summer heat. In Nebraska and Kansas, there were many contestants who couldn’t stand the heat in the Pullmans and opted instead for prairie grass. In Salina, Kansas, on the 29th, the temperature was 104 in the shade, which induced many to sleep outdoors in chairs or on the grass.

Depending on which newspaper account you read, the tour’s start saw somewhere between 43 and 50 contestants, as well as a group of non-contestants. The Rapid truck was part of the latter group and would carry contestants’ baggage. It’s interesting to note that Goodyear provided “air bottles’ — steel bottles filled with compressed air — to all participants free of charge for use in inflating flat or low tires.

On July 12th, following a blast from a Civil War cannon at Cadillac Square, the cars were released at one-minute intervals. The very first car on the road, though, with a two-hour lead, was the “trailblazer” car, which would lead the parade of contestants through the entire tour. It was also called the “confetti car,” because it dropped confetti on the roadway behind it to show the way. Here’s a photo link showing the “confetti car” from the ‘08 Glidden Tour: https://forums.aaca.org/topic/255714-1908-glidden-tour%E2%80%9Cpathfinder%E2%80%9D-%E2%80%9Cconfetti-carto-make-sure/ . I wonder how much confetti the ’09 tour would have needed for a road trip of over 2600 miles?

The tour set off west from Detroit, hugging the shores of Lake Michigan, with the first overnight stop being Kalamazoo. Succeeding overnight stops would be in Chicago, Illinois, Madison and La Crosse, Wisconsin, and Minneapolis, Minnesota. Following a two-day rest in Minneapolis on the 17th and 18th, drivers and crews would head south, overnighting in Mankato, Minnesota, Fort Dodge and Council Bluffs, Iowa, and Kearney, Nebraska. Out of Kearney, their first overnight stop in Colorado would be Julesburg on July 23rd. On the 24th they would travel to their next stop, Denver, and there enjoy their second two-day rest. In driving from Julesburg to Denver, they would pass through the eastern Colorado towns of Sedgwick, Red Lion, Proctor, Sterling, Hillrose, Brush, Bennett and Fort Morgan.

On July 27th, following their rest in Denver, the drivers and their crews would make tracks for Colorado Springs, passing through Littleton, Sedalia and Palmer Lake on the way. In Colorado Springs they would be entertained by a reception committee and be given the opportunity to “admire Pikes Peak.” This of course is not the same as climbing Pikes Peak, which indicates that the Pikes Peak climb was not a designated part of the tour. Thus, it appears that at this point the Rapid truck and crew broke off from the rest of the tour to make the climb.

After leaving Colorado Springs on July 27th, the contestants drove through Falcon, Calhan, Ramah, Resolis, Limon and Genoa to reach Hugo, and after their overnight stop there proceeded through Sorrento, Kit Carson and Cheyenne Wells into Kansas, with an overnight stop in Oakley. The next day would see them progress from Oakley to Salina, and on July 30th they would cross the finish line in Kansas City, Missouri.

Two cars finished with zero penalty points. Both were Pierce Arrows, one driven by W.F. Winchester in Pierce Arrow car no. 9 and the other by J.S. Williams in Pierce Arrow car no. 108. Winchester won the Glidden Trophy for the most roadworthy touring car, and Williams won the Hower Trophy for his achievement in a runabout. Jean Bemp, in a Chalmers-Detroit no. 52, would win the Detroit Trophy with a score of 14.2.

REFERENCES:

- “A.S. Donaldson Dies in Denver,” Escondido Times-Advocate dated December 13, 1935, www.newspapers.com at https://www.newspapers.com/image/legacy/567035660/?article=1c3e412c-b5fe-4a11-80f4-750fc2bfd7fc&focus=0.67510915,0.015468513,0.8321862,0.63381284&xid=3355

- “Commercial Cars in Denver,” by C. M. Smyth, Cycle and Automotive Trade Journal dated January 1, 1912, Google Books at https://books.google.com/books?id=56cyAQAAMAAJ&pg=RA1-PA294&lpg=RA1-PA294&dq=donaldson+%26+howard+commission+company+rapid+cycle+and+automobile+trade+journal&source=bl&ots=oaM-W_wPRO&sig=ACfU3U1jFBAlAJxL5nu2kMi4LDsfj6p60w&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjl7ZKl0c74AhVzEEQIHQzBD2oQ6AF6BAgiEAM#v=onepage&q=donaldson%20%26%20howard%20commission%20company%20rapid%20cycle%20and%20automobile%20trade%20journal&f=false

- “Detailed Route and Checking Stations of the Glidden Tour, Detroit to Kansas City,” St. Louis Post Dispatch dated July 11, 1909, www.newspapers.com at https://www.newspapers.com/image/legacy/138921181/?terms=glidden&match=1

- (Ad) “The Donaldson and Howard Commission Company,” Western Colorado: A Fruit, Farm and Sugar Beet Journal dated August 10, 1899, Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection at https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=WNC18990810-01.2.10.1&srpos=1&e=——-en-20–1–img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA-donaldson+and+howard——-0——

- “THE FIRST CENTURY OF GMC TRUCK HISTORY,” compiled by Donald E. Meyer at https://www.gmheritagecenter.com/docs/gm-heritage-archive/historical-brochures/GMC/100_YR_GMC_HISTORY_MAR09.pdf

- “Flashback Friday: The Gliddenites are Coming! Nebraska and the 1909 Glidden Tour,” History Nebraska at Flashback Friday: The Gliddenites are Coming! Nebraska and the 1909 Glidden Tour | History Nebraska

- “Glidden Tour,” Wikipedia.org at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glidden_Tour

- “The Glidden Tour Years,” Pierce-Arrow Society at https://www.pierce-arrow.org/pierce-arrow-history/the-glidden-tour-years/

- “Glidden Tourists to be in Julesburg Night of July 22,” The Julesburg Grit-Advocate dated June 18, 1909, Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection at https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=GAD19090618-01.2.4&srpos=1&e=——-en-20–1–img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA-julesburg+glidden——-0——

- “The Glidden Tour Of 1909,” The Museum of Lake Minnetonka at https://steamboatminnehaha.org/the-glidden-tour-of-1909/

- “Glidden Trophy Won by Pierce Arrow Car,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat dated August 2, 1909, www.newspapers.com at https://www.newspapers.com/image/legacy/572083754/?terms=glidden%20tour&match=2

- GMC Celebrates its 100th Anniversary in 2012,” PickupTrucks.com at https://news.pickuptrucks.com/2011/12/gmc-celebrates-its-100th-anniversary-in-2012.html

- (Ad) “How to Bring Up a Tire on a Bottle in Thirty Seconds,” San Francisco Call dated January 3, 1909, California Digital Newspaper Collection at https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SFC19090103.2.108.2&e=——-en–20–1–txt-txIN——–1

- “Max and Morris Grabowsky founded Grabowsky Motor Company in Michigan in 1900,” dated June 4, 2022, Just a Car Guy at https://justacarguy.blogspot.com/2022/06/max-and-morris-grabowsky-founded.html

- “The Other Side of It,” the Kansas City Times dated July 31, 1909, www.newspapers.com at https://www.newspapers.com/image/legacy/653551991/?terms=glidden&match=1

- “Rapid,” cartype at https://cartype.com/pages/7153/rapid

- “Rapid Motor Vehicle Company,” WikiMili at https://wikimili.com/en/Rapid_Motor_Vehicle_Company

- “Reliance Motor Car and Truck Company,” at https://www.shiawasseehistory.com/gmc.html

- “Rockville Center GMC,” Facebook at https://m.facebook.com/RockvilleCentreGMC/photos/on-august-1-1909-a-rapid-f-406-b-a-gmc-predecessor-was-the-first-truck-to-reach-/10154315905003277/

- “Tonneau ,“ www.wikipedia.org at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tonneau

- “William C. Durant,” www.wikipedia.org at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_C._Durant

- “Yellow Coach – 1923-1943- GMC Truck & Coach Division, General Motors Corp. – 1943-present – Detroit, Michigan,“ Coachbuilt at http://www.coachbuilt.com/bui/g/gm/gm.htm

- 1894, 1895, 1909 and 1917 Denver City Directories (at www.ancestry.com)

- “1908 Glidden Tour*“Pathfinder” /*“Confetti Car,” Antique Automobile Club at https://forums.aaca.org/topic/255714-1908-glidden-tour%E2%80%9Cpathfinder%E2%80%9D-%E2%80%9Cconfetti-carto-make-sure/

- “1909 Glidden Tour – Indianapolis Star,” The First Super Speedway at https://www.firstsuperspeedway.com/articles/1909-glidden-tour-0

- 1910 and 1920 Censuses (at www.ancestry.com)

- 1911 Business Directory listing for Denver at http://files.usgwarchives.net/co/denver/directories/1911-denvercd.txt

Pingback: Jacks Old Photos of Colorado